This veteran of Close Encounters is the scientist trying to heal his computer creation, the murderous HAL, as he faces the vastness of space in the year we make contact, 2010.

By LEE GOLDBERG

There's something scholarly about Bob Balaban. According to an MGM spokesman, "few actors can project a feeling of intelligence better than Balaban."

Perhaps it's the beard. Or the glasses. Whatever "it" is, it has led to a slew of what he calls "smart parts," as scientists in films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Altered States, and lawyer roles in such recent movies as Prince of the City and Absence of Malice.

And now his cerebral image has propelled him into deep space as computer genious Dr. S. Chandra, father of HAL, in director/writer/producer Peter Hyams' 2010, the long-awaited sequel to the Stanley Kubrick-Arthur C. Clarke epic, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

"Yeah, I've been labeled as smart," Balaban says with a shrug, the beginnings of a grin on his face. "It's better than people saying I look like a scowling maniac."

Balaban read the Clarke novel shortly after he read Hyams' screenplay version of 2010 and liked the adapatation. "I like to think of the book as an outline for a good movie," he says. "I liked the book and I think it provided a powerful overstructure. The movie improved on the book by expanding both the characters and their relationships."

The emphasis on character is the key difference between 2010 and 2001, a film that has become a milestone in motion picture history for its daring, philosophical storyline and inauguration of sophisticated visual effects.

In 2010, Roy Scheider plays scientist Heywood Floyd, who joins two other American scientists, John (Buckaroo Banzai) Lithgow and Balaban, aboard a Russian spacecraft bound for Jupiter, where the derelict Discovery drifts beside an awesome black monolith of alien origins. The crew hopes to uncover the fate of astronaut David Bowman (Keir Dullea), the malfunction that turned HAL into a murderous computer, and the secret to the alien monolith.

Meanwhile, the cold war is heating up on Earth and World War III seems imminent. And, in deviation from the book, the friction also extends to the Russian and American crew members.

|

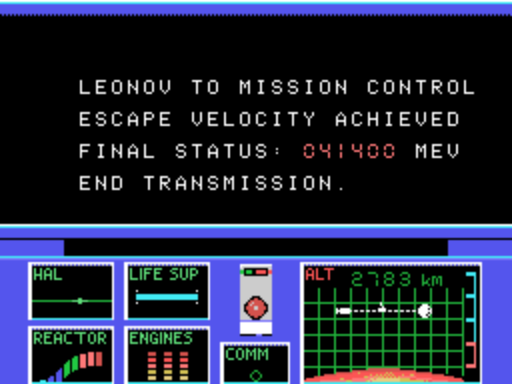

| Chandra (Bob Balaban) uses ski-lift cable to travel from the Leonov to the abandoned Discovery. |

"I would like to have played an Indian," he adds, "although Indian people, and rightly so, would have resented that casting. I thought, in essence, the screenplay maintains his devotion to HAL and his affection for HAL. That was the most important part of the character."

Balaban had the opportunity to see how the screen adaptation fared with Clarke when the author visited the 2010 set at MGM Studios in Culver City, California.

"I was glad he came on my last day of shooting," the actor admits. "I was nervous that he might observe me playing Chandra and think, 'No, no, no, that's not my idea of Chandra at all.' I expected to be intimidated by him. But, he turned out to be a very funny, droll person. Here was this very accessible man, charming and kind, and I thought he was great."

A Human Sequel

Few sequels amount to anything more than pale imitations of the originals. Some sequels overcome that obstacle, but still falter as worthwhile films in their own right. Balaban believes, as one might expect him to, that 2010 is different.

"To me, 2010 is a good sequel. It's very different from the first one, but there are enough elements in it from 2001 to involve people who are in love with that film - and enough new material to attract a whole new crop of people who have never seen 2001," Balaban says. "2010 almost exists in a different genre than the first one did. This one is about humanity, humans and their adventures and misfortunes, while 2001 was a wonderful movie that was more about metaphysics."

Stylistically, 2010 owes less to 2001 than it does to the increased technological sophistication of movie audiences who are accustomed to seeing dazzling effects and real-life space journeys.

"The time is different now," he says. "We are much more advanced, we've done many of the things they were just thinking about when 2001 was released. In some ways, I think 2010 is much more grounded in what we are familiar with already. We all know what spaceships look like, we've seen astronauts walking in space, untethered, we've seen the Moon. So, this movie, in some respects, must be much more realistic than 2001 and rely less on hardware and more on character."

He sees 2010 as an original film, a movie "in the same ballpark but not a sequel," Balaban notes. "The trap of a sequel is that the central focus becomes tying up all the loose ends and not presenting a compelling and interesting story in its own right. I think this motion picture will stand on its own."

None of the filmmakers or cast members really expects 2010 to duplicate the sociological effects that 2001 had. That reaction is not something you can engineer in a soundstage.

|

| Chandra is reunited with his brainchild, the HAL 9000, and reanimates the potentially lethal computer. |

"When 2001 opened," the actor says, "it had very little appeal at first. It grew out of cult status and somehow hooked into a whole cultural chain of events that was occuring. That didn't just happen the month the movie was released."

Studio execs entrusted the mammoth project to Peter (Outland) Hyams, who tackled 2010 in pure Kubrickian fashion by assuming many of the same responsibilities himself. Hyams not only directed from his own screenplay, but served as the cameraman and produced the film. And, from Balaban's perspective, Hyams has pulled it off.

"Monumentally so. He achieved the one, highly impossible thing when doing a movie of this size and scope on such a tight schedule; he maintained a wonderful good humor," Balaban says. "And that is very important to actors in films like this one. The danger of a film with many effects is that you will not be cared for by the director. Peter never lets that happen. I don't know how he managed to do it, racing between two different soundstages and dealing with all the other things he had to think about with which we never had to concern ourselves."

But Balaban is interested in those "other things," since he's now embarking on his own directorial career. He helmed a critically acclaimed short film several years ago about "a day in the life of a special effects man."

SFX1140 was screened at Filmex and at the Museum of Modern Art. If featured Mandy (Ragtime) Patinkin, Richard (Close Encounters) Dreyfuss and Wallace (Strange Invaders) Shawn.

"On the basis of that film, George (Dawn of the Dead) Romero offered me a job directing the pilot for his syndicated horror anthology Tales of the Darkside," he says. "It was like doing a little movie. It's not like directing an episode of a TV show where you know all the characters already and they all talk the same way. I can show this episode, 'Trick or Treat,' to people, and it stands up as a short movie."

Balaban's background in movies is firmly rooted in his family lineage. His father owned a chain of 175 Chicago-area movie theaters, his uncle was a Paramount Studios president and his grandfather once served as MGM's head of production. When Balaban was six-years-old, he was already making movies with his dad's 8-mm camera.

Balaban studied English first at Colgate University, then at New York University, where he chagned his major to film. His girlfriend, Lynn Grossman, suggested that he audition for the role of Linus in an off-Broadway musical called You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown. He got the role and later married Grossman, now a TV writer.

|

| Inside HAL, Chandra (Bob Balaban) inserts new program elements, changing the thinking machine's priorities. |

After bouncing around Broadway, he drifted on to TV guest shots and made his film debut in 1969 as a young homosexual who propositions Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy. Close Encounters, Altered States and other films followed (as noted in an interview with Balaban in STARLOG #44).

A HAL Scene

Currently, Balaban is developing a "medium-size comedy" to direct for MGM. He is looking forward to more work on the other side of the camera. But on 2010, Balaban's job was strictly acting, though he paid close attention to Hyams' style.

"I was more aware of what Peter's problems might be. I think the first way to get yourself hated, though, is to offer advice. I just did my job and I watched and I learned," Balaban says. "I didn't find myself second-guessing him, but I am more aware of things that, before I began directing, I wasn't much aware of."

"This reminds of a story," he pauses. "When [actor/director] Francois Truffaut worked on Close Encounters, the first thing he did, because we were all scared of him in one way or another, was to go up to Steven Spielberg and say, 'You're the director, I'm here to be an actor. I'm here to help you and be quiet and patient and obedient and not get in your way.' It was a wonderful speech."

Balaban finds some similarities between Hyams and Spielberg. Both, he says, are "actors' directors."

"I think they feel that while they are experts at what they do, they have respect for actors and they treat actors as people who might actually know something," Balaban says. "That's a very nice thing. I mean, you can go too far in that respect. They're directors who are interested in what actors have to say, but they are foolishly over-ruled by them. They're interested in what actors have to bring to the part. They see that input as a valuable part of making the movie. My favorite directors are those who know when it's important to collaborate and when to say, 'No, I want it this way and that's the way it's going to be.' "

Balaban didn't have much of a chance to work with Scheider, Lithgow and the rest of the cast, which includes Helen (Excalibur) Mirren and Elya (Moscow on the Hudson) Baskin. Most of his scenes were with an inanimate box full of fluorescent lights and colored plastic that, with a little movie magic, becomes HAL.

"It wasn't as difficult as you might think," Balaban says. "Peter pre-recorded all of Douglas Rain's dialogue as HAL. Rain is a very good actor. So, they played his voice when I did my scenes. It was very much like acting with another human being, except HAL never forgot his lines or tried to break me up. And if I was really good, he didn't goof up."

"Strangely enough," he adds, "I had no sense of acting with a recording. As far as I was concerned, if felt like he changed his performance from take to take."

The only problems that arose were technological. All of Balabans's "weightless" exploring inside HAL played havoc with the actor's equilibrium.

"After two days of being twisted around inside HAL, my inner ear got affected and I got a horrible case of vertigo," Balaban says. "That was unusual. The flying sequences were fun. It has always been a great dream of mine to fly in a movie, a play or somebody's house. Anywhere. It's been great fun, if you overlook the geophysical discomforts, hanging from wires and being poked through sets. Occasionally, I would catch a glimpse of myself reflected in glass and get thrilled about how magical it was. I didn't feel weightless. You can feel the harnesses tugging against you. I felt like a 3000-pound lead brick."

Which is what he hopes 2010 won't be at the box office come December 7.

"I'm just dying to see the movie," Bob Balaban says. "One never knows what a movie of this scope will look like. Seeing Close Encounters, one of my favorite movies ever, was like seeing a film I had never been in because the effects were so powerful. I suspect when I go to see 2010, I will feel like the audience. Everything will be a complete surprise."

(This article was originally publish in Starlog Magazine, 1984. Copyright © 1984 Starlog.)

_01.png)

_03.png)

_09.png)